By Vanessa Lowe and Peter Winslow of POWER Interfaith, and Dieynabou Barry, Climate Justice Lead at PowerSwitch Action.

Dieynabou: Vanessa and Peter, thanks so much for giving us a sneak peak into POWER’s work with the Philadelphia Public Banking Coalition! Let’s start with the basics: What are public banks, how are they different from private banks, and how do they serve the public good?

Peter: The biggest difference is who the bank serves. Instead of being owned by private individuals, a public bank owned by the people.

With a private bank, the purpose of the bank is to deliver profit to the shareholders. With a public bank, the purpose of the bank is to support the overall wellbeing of the community.

Now of course, public banks have to be operated prudently so they can sustain themselves, but the motivation is very different. And because of that, the institutions operate very differently. In Philadelphia we expect the public bank to be owned by the people, as an act of participatory democracy.

Vanessa: I think it’s helpful for folks to understand that this is not a traditional bank where they’re going to walk in and open a checking account. It’s not a retail bank or credit union, but it has similarities to a credit union in that it’s controlled by the folks whose money is in the bank.

This is an institution that is allowing the city or the state essentially to have autonomy and act in the public’s best interest. What I love about public banks is that we don’t have to depend on those larger, private, profit-focused banks which put our money at risk like we saw during the 2008 crisis.

That part is critical, especially in cities like Philadelphia: major cities with large communities of color and particularly African American populations.

When you look at the kind of projects that private banks are funding, and what they’re doing with their money, and the way they treat people, it’s clear that they don’t think of us as their customers. What they fund is often contrary to what the residents of the city need.

So to be able to take that control back — the billions of taxpayer dollars that we’re sending them to just hold and do with what they will, and the millions of dollars we’re paying annually on things like bonds — that’s powerful.

These are our tax dollars. With public banks, we’re keeping them in our city as opposed to sending them to Wall Street.

Peter: What we’re focused on in Philadelphia and in most places where the public banking movement is making progress is not retail banking. It’s partnerships with other financial institutions that will direct resources and leverage the funds within the public bank with other resources in the community.

We want credit to be more fairly available, we want to identify gaps in credit availability, analyze them, come up with innovative solutions, and implement those solutions to level the playing field.

Dieynabou: Are there other public banks operating in the US?

Peter: Yes! One example everybody looks to is the Bank of North Dakota. It’s the longest-established public bank in the United States. It was established in 1919, after a farm labor coalition passed legislation to establish it. The people in North Dakota love the Bank of North Dakota. One of their programs that is extraordinarily popular and extraordinarily successful is their higher education student loan program.

Vanessa: An interesting point about the Bank of North Dakota: That state really came through the 2008 financial crisis relatively well, because they did not have as much of their assets sitting up there with Wells Fargo and the rest of Wall Street. They were managing their own money.

Dieynabou: Got it! Can you tell us about how POWER started working in coalition to create a public bank in Philadelphia?

Vanessa: My earliest memory of this project is from about ten years ago. The national volunteers who are passionate about this issue got together and created a nationwide conference here in Philadelphia on public banking. That was my introduction to it. I think that’s where our official coalition got started.

Peter: As Vanessa mentioned, the financial crisis in 2008 brought us close to self-destruction of the world economy as a result of fundamental problems with the financial system.

The system we have is fragile, and it’s dangerous for all of us to have it continue this way. So the experience of 2008 was a wake-up call for many of us. People started talking about alternatives, ways to reexamine the underlying ecosystem, and the role that banks and money creation play in that fragility.

Our coalition here in Philadelphia is made up of people and organizations that have been locked out of the benefits of the current system — locked out of access to credit, and to funding, and to the opportunity to build a stable foundation.

We have a history of redlining in Philadelphia as in most parts of the country. That legacy persists in de facto redlining today. We believe there are fairer ways that that credit can be distributed. We now have a critical mass of people in Philadelphia who are thinking about this problem.

We found a champion for the cause within the City Council, our Councilmember-at-large Derek Green. With his guidance from a legislative standpoint, we’ve gone through a variety of steps: a feasibility study that was commissioned by the city to look into public banking here, public education and outreach, forums, summits, and other activities to make this project feasible and accessible for the people of Philadelphia.

Vanessa is the co-host of a monthly public conversation called “Financing Philadelphia’s Future with Councilmember Derek Green.” That’s been a hugely successful way to invite the public into the process as we’ve worked to establish the bank.

Dieynabou: And what’s the most recent news coming out of the City Council in Philadelphia?

Peter: In March, we passed a bill establishing the Philadelphia Public Financial Authority — which is the precursor to the public bank. The next step is to set up that Authority: appoint a board of directors, and get the City to provide some start-up funds. We’re also asking the City Council to capitalize the financial authority so that it has funds to work with. That means authorizing $75 million through a general obligation bond from the city, which would provide the funds for the financial authority to manage. Luckily, and because we’ve been working on this and building support for years, we have very strong support for the project within City Council.

We’ve recently received news that the Mayor is refusing to implement the legislation, which was enacted with a veto-proof majority. We think that such intransigence displays distain for representative democracy as well as for participatory democracy. Nevertheless, now that Mayor Kenney has ended his previously inscrutable silence on the subject, we hope he will be willing to engage in a productive discussion of the merits of the Financial Authority. If everybody proceeds in good faith, I’m confident our cause will prevail.

The movement to democratize money will encounter many obstacles. So, there are many next steps that will be needed to navigate a course forward.

Disruption of the status quo to achieve dynamic progress requires courage and imagination as well as mutual respect and trust. We need leaders. We expect our elected officials to be our champions. But, we are neither naive, impractical, nor lacking in independent agency. Our work continues.

Dieynabou: Thanks for that update Peter. Can you speak about how winning a public bank connects to POWER’s broader vision for social justice, racial justice and climate justice?

Vanessa: Access to loans and financial services is a racial justice issue.

The public bank will be collaborating with existing institutions to make sure that loans are getting to Black and Brown folks who have been locked out of our financial system.

There’s a whole network of institutions called CDFIs (community development financial institutions) that were created about 30 years ago and have grown into a powerful, effective, proven model. They serve folks who are low income with financial services, and they fund projects that support stronger communities for underserved areas.

Our public bank will be working with a coalition of CDFIs that already exist. And we love CDFIs and are thrilled to be working with them, and at the same time, not all of them are targeted to serve some of the folks who have been traditionally left out of financial services. So that’s where the public bank comes in and why this collaboration is critically important.

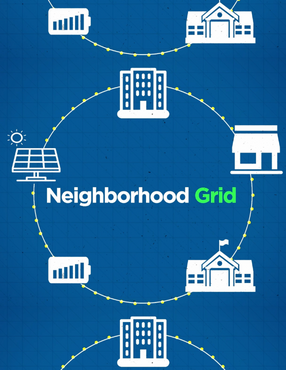

Peter: And on the environmental justice front: There are a variety of ways in which the climate crisis can be mitigated and action can be taken at the local level with support from the financial authority and public banks. As Vanessa was saying, we’re very strongly committed to the partnership model. For instance, in Philadelphia we have a Philadelphia Energy Authority, which has recently started a Philadelphia Green Capital Corp. It’s essentially a green bank — and creating an alliance with the financial authority can help support everything from solar to energy efficiency projects and carbon reduction.

We also know that there is going to be a huge energy transition coming, away from gas. That transition will require funding, and the financial authority can help make that process as smooth as possible.

Dieynabou: Thank you so much for your time! We can’t wait to see what comes next.

...