In Massachusetts, our affiliate Community Labor United (CLU) is co-leading efforts to democratize energy and build climate resilience through the development of microgrid projects in Boston’s Chinatown and Chelsea neighborhoods. Our Climate Justice Lead, Dieynabou Diallo, sat down with Lee Matsueda (Executive Director of Community Labor United), Sari Kayyali (Microgrid Manager at Resilient Urban Neighborhoods-Green Justice Coalition), Lydia Lowe (Executive Director of Chinatown Community Land Trust), Maria Belen Power (Associate Director of GreenRoots), and Jen Stevenson Zepeda (Associate Executive Director at Climable).

Dieynabou: Thanks so much to all of you for making the time to chat. Can you tell me how the microgrids project got started, and how it has benefited from a coalition model?

Lee: Everyone speaking here today is part of an awesome team that we have – the Resilient Urban Neighborhoods-Green Justice Coalition Partnership – that's really helping execute this plan around the microgrids.

Since 2005, CLU has been bringing together community labor partners in Greater Boston to move different campaigns. In 2008, we set up this group called The Green Justice Coalition, and that was about building up a broader base of support to create a more sustainable, equitable, clean energy economy. That included leveraging resources to make sure people could save dollars on fuel costs, get weatherization done on their homes, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2016 The Green Justice Coalition responded to a request for proposal that was put out by the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center. Through that (and in concert with the Chinatown Progressive Association, Chinese Progressive Association, and GreenRoots), we started talking about what it would look like for us to not just run campaigns, but actually invest energy and time into developing a microgrid.

Through it all, we got to meet an amazing set of folks, like the Resilient Urban Neighborhoods Team and other partners, who have provided the technical expertise, namely information on how to build and develop microgrids. Ever since then, we've been working together to create resilient and thriving communities with energy systems that we can depend on.

Dieynabou: How does a microgrid work, and how does this microgrid project differ from others?

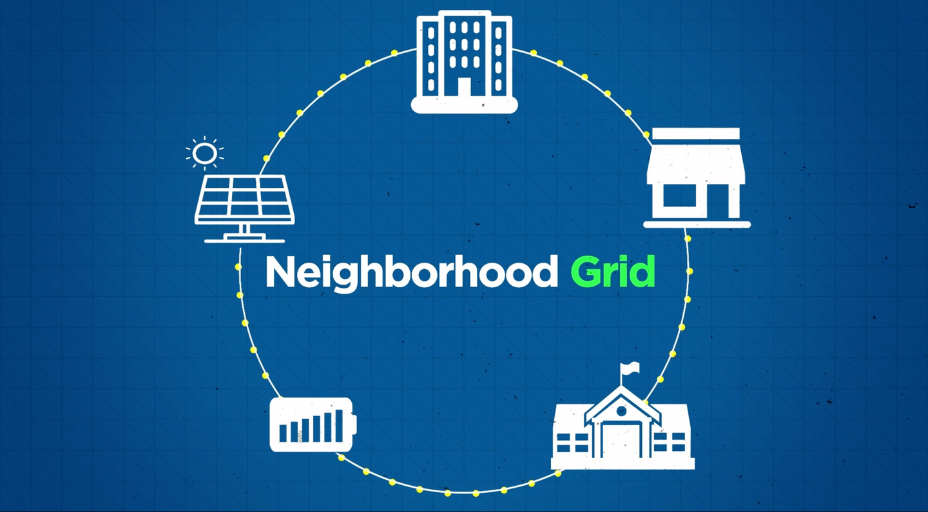

Sari: In a traditional electric grid, there is a power plant some distance away from where people live that generates all of a community's electricity. That electricity is distributed over long distances and then delivered to homes, businesses, and other buildings within a local area. The way a microgrid differs is it generates the electricity onsite. A traditional microgrid will be the size of a college campus or a hospital, and that brings a number of advantages — you lose less energy in transmission, and can save money by generating your own power when electricity rates are highest.

Our model differs from a traditional microgrid in that we're not looking to interconnect participating buildings. Instead, we intend to install the means of electricity generation at every single building, whether that's via solar panels or a clean diesel generator. We also plan to install battery storage, which will allow us to store that energy.

Jen: One of the unique features of our microgrids is that they use as many clean and emissions-free technologies as possible. They both create clean power and make communities more climate resilient. Many power outages are caused from damage to transmission lines – trees falling on them, wind, ice, and other extreme weather events. The grid is already old to begin with. So, the closer we can place a generating source to where the energy is consumed, the more reliable that electricity is.

This is critical in times of emergency. We've seen how frontline communities suffer first and worse when these big climate events happen. We’re working to get ahead of the game and build these microgrids before the worst of these events come to Boston. We also think this can serve as a model for other communities.

Dieynabou: At the center of this project are two neighborhoods, Chelsea and Chinatown. Can you share why the microgrid project is so important in these communities?

Lydia: The Green Justice Coalition decided to focus on Chelsea and Chinatown because of a commitment to environmental justice and social justice. We believe in democratizing energy and decision-making, and trying to bring the benefits of new technology to communities that are most vulnerable to pollution and climate impacts, but don’t have the same access to energy efficiency programs. Chinatown is an environmental justice community for a couple of reasons. It's the hottest neighborhood in Boston – it’s a heat island, it's very dense, and it’s home to a low-income community that has very few trees and very little open space. Recently, The Boston Globe highlighted what that means for tenants in Chinatown.

Chinatown is also at the intersection of two interstate highways and has suffered a lot of displacement historically because of institutional expansion and highway construction. That has contributed to many decades of health impacts – it’s one of the most impacted neighborhoods in terms of air pollution. It was also built on reclaimed land, so it is very susceptible to flooding. We know that major weather events are on the horizon, so we think microgrids are going to be increasingly important in Chinatown’s near future.

Our recent heat wave has made people even more aware of climate change and all of the different dangers related to it, and we think that there are immediate benefits that the microgrid can bring in addition to resilience. We see opportunities to pair the microgrid with other kinds of energy efficiency work in different buildings, which could bring efficient heating and cooling to buildings that haven't had that kind of benefit before. In Phase 1 of our project, all of the buildings that we're looking at are low-income housing and affordable housing. We're including at least one smaller three-decker row house – which is actually owned by the Chinatown Community Land Trust – as an important model of what can be done with smaller properties. We’re looking into larger buildings as well, like the local elementary school.

Sari: Chelsea is also an environmental justice community, it has a large immigrant population and is also a coastal city where much of the city is at risk of flood. Many of the same conditions that exist in Chinatown also exist in Chelsea.

Maria Belen: Chelsea is the smallest city in the Commonwealth, yet the second most densely populated after Somerville. 24% of residents live below the poverty level and over 70% identify as people of color. We don’t think it’s a coincidence that Chelsea carries an immense industrial and environmental burden for the entire region. In Chelsea Creek alone, there are tanks that hold 100% of the jet fuel for Logan Airport, 80% of the region’s home heating fuel, 70% of the region’s gasoline, and 400,000 tons of road salt that serve over 350 communities in the Northeast. This is not a typical situation for communities in Massachusetts—this happens in low-income communities and communities of color. But, fortunately, Chelsea is incredibly tight knit and as a result of base-building and community organizing efforts, we have connections and relationships with elected leaders and decision-makers in key industries. We have a history and a practice of holding them accountable. So in pursuing a municipally owned microgrid, we are creating one that is managed, owned, and operated by the city and therefore more accountable to ratepayers and residents.

Dieynabou: Can you tell us more about community governance and the latest on the project?

Lee: We're at an exciting phase right now, and we’ve come so far – from the concept to incorporating to create a B Corp, Chinatown Power, that's well positioned to have not just governing power, but also decision-making power over what's happening in that neighborhood. This means residents will decide which developers to work with and what parts of the project to prioritize, while owning assets like the solar panels or batteries. A version of this model is playing out in Chelsea as well.

Maria Belen: Energy justice and energy democracy have been a part of our work for a long time. We worked with Chinatown at the beginning, right after The Green Justice coalition was created, on weather station pilots. We’re pursuing the municipal model in Chelsea, so it is a little bit different than Chinatown. In Chelsea, our model will include a board or some sort of public entity that will manage the microgrid with representation from the community and stakeholders.

Jen: Community governance is a key part of what makes our microgrid project different. And it’s an important way to build climate resilience. For example, when there's a power outage, we can have reliable electricity in communal buildings as a form of resilience. That way people with any type of mobility issue, people who have medication that needs to be refrigerated, people who need a reliable means of communication, and anyone else have somewhere to go. People can use phones, charge medical devices, use the elevator, have emergency lighting and refrigeration available, and more.

Lee: Now that we’ve made connections in both neighborhoods with buildings that want to be a part of this microgrid, it's about putting the idea into motion and getting the dollars to support the beautiful vision that's rooted in these communities and the leadership of these communities. That’s the big push we’re focused on now.

Maria Belen: We talk a lot about fighting the bad while building the good. We're fighting archaic and dangerous infrastructure in our communities, while supporting and building the solutions. A community-owned microgrid is one of them.