Note: This article was produced by the California Partnership for Working Families: Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE), Center on Policy Initiatives (CPI), East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy (EBASE), Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE), Orange County Communities Organized for Responsible Development (OCCORD), Warehouse Worker Resource Center, and Working Partnerships USA (WPUSA)

The Post SB-827 Landscape

SB 827, the most attention-grabbing bill of the 2018 California legislative session, died in its first hearing. While there are many theories as to why the bill died, it’s clear that it was not only because of the power and wealth of obstructionist NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) homeowners, but also because the bill drew staunch opposition from the very people it claimed to help: low-income renters, workers and communities of color on the front lines of the housing crisis. Looking forward to a new legislative session, the defeat of SB 827 provides some important lessons in what went wrong and how urbanists and abundant housing advocates can do better by listening to and partnering with communities of color, who have deep knowledge and lived experience from generations of struggle and power-building against displacement and gentrification. These advocates can also join together with low-income and working class communities and center their priorities, like affordable housing construction and preservation, good construction jobs with decent wages and working conditions, and focusing development in high-resource exclusionary areas and not just neighborhoods that are already taking on most of housing production.

NIMBY vs. YIMBY: Who is not included?

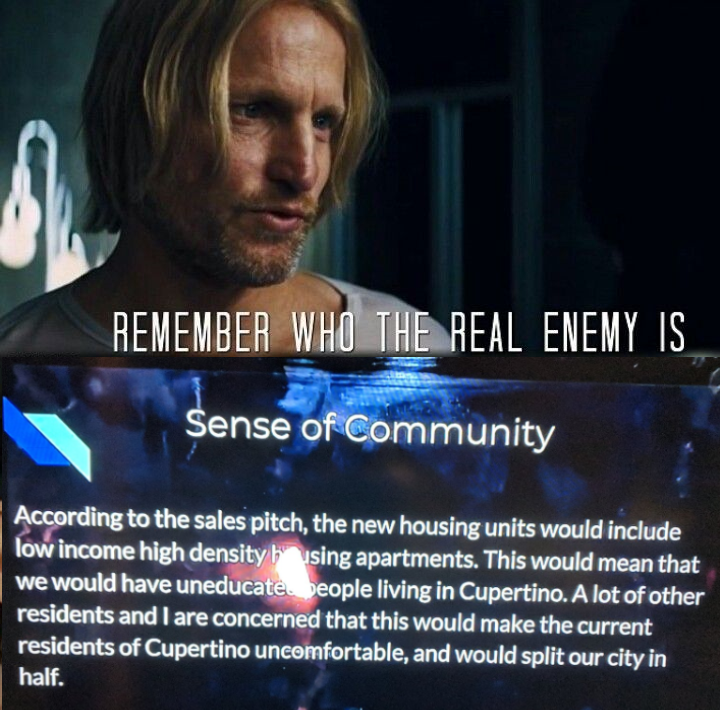

To move forward, it’s important to acknowledge the problems with the process the last time around. The issue began with who was at the table when the bill was crafted. Proponents of SB 827, who have adopted the title YIMBY for “Yes In My Backyard,” have framed the housing debate as having two types of people: the first are NIMBYs, predominantly older, white, middle and upper-class homeowners, who have a chokehold on local neighborhood councils and planning commissions and prevent any new housing from being built that might cause them traffic or parking problems or worse, hurt their property values. The second are an emerging movement of YIMBYs, whose base is mostly young, mostly white professionals who rent, and many of whom have recently migrated to major coastal cities where jobs are heavily concentrated, but struggle to afford astronomically-priced market-rate apartments, with homeownership far out of reach. While many YIMBY organizations have supported tenant and low-income worker priorities like the repeal of Costa Hawkins and the passage of Proposition C in San Francisco, the bulk of their focus has been on lowering barriers to development in cities.

Unfortunately, this understanding of the world leaves out the people who actually make up a majority of the urban population in California: working-class communities of color whose families have lived in our cities for decades, while middle-class white families fled the urban core for faraway suburbs. Because of discriminatory and predatory mortgage lending by banks backed by federal policies like redlining, places like East Oakland and South Los Angeles historically became home to communities of color blocked from living elsewhere, often shut out of homeownership and forced to rent from predatory landlords. Despite low-density official zoning, these neighborhoods typically have high population density and high transit ridership because of economic necessity, with extended families often living together in modest homes and riding the bus to work.

These communities, who are on the front lines of California’s housing crisis, are not NIMBYs. In fact, they have spent many generations fighting against exclusionary, racist housing policies that kept them out of certain neighborhoods, long before YIMBY ever became a rallying cry. In Los Angeles, many of the very same groups just played a crucial role in defeating a NIMBY proposal to halt new housing development in the city through the failed Measure S in 2016. Communities of color have certainly seen the worst of discriminatory and restrictive government housing policy in the hands of wealthy white homeowners who have battled integration initiatives since the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960’s. But they’ve also seen the worst of the speculative housing market and know that if allowed to, the real estate industry and their Wall Street financiers would tear down or buy up every single one of these neighborhoods to replace low-income communities of color with more desirable customers.

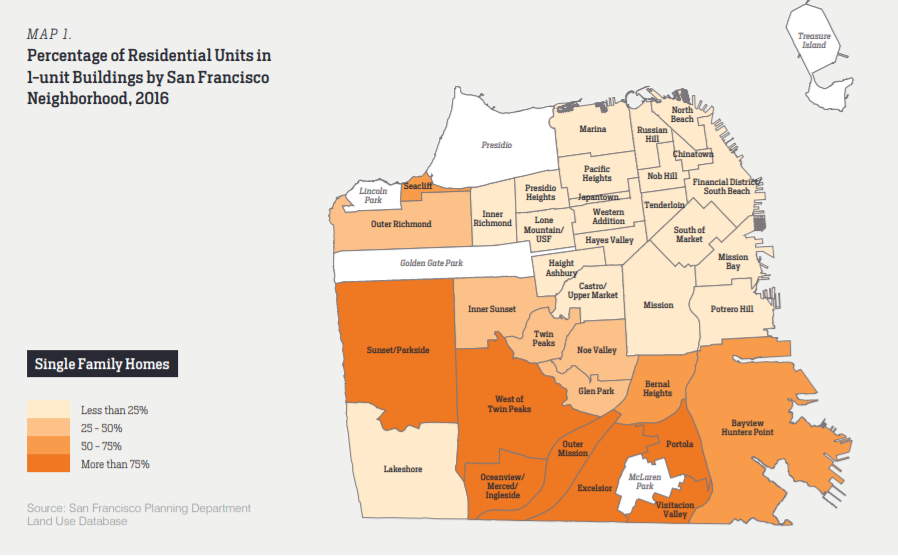

Housing near transit: The Density Paradox

These communities were largely left out of the policy development behind SB 827, despite the fact that their neighborhoods were most at risk of displacement. These low-income neighborhoods of small houses and low-rise apartments tend to be the most affordable in their regions due to their older housing stock and the racial stigmas associated with them, and are often served by a network of high-frequency bus and rail lines due to their higher levels of transit ridership. Yet their proximity to the jobs and transit in the urban center has spurred a speculative race to own the land beneath these long-neglected neighborhoods that have recently become “hot” in the 21st century economy and to house young affluent urban-oriented tech workers, resulting in long-time residents being displaced to far-flung suburbs or out of state. These neighborhoods are not seeing the benefit of this “return to the city,” not even in the form of jobs; the housing sector has some of the lowest average wages of any construction field. They are not given the opportunity to access or preserve affordable housing as part of these new investments, as developers use loopholes or pressure politicians to get around having do their part to house working people in the state. They are also painfully aware of the geographic inequality of their housing being bought up and redeveloped for the young professionals moving to cities, while rich single family home neighborhoods and enclaves like West Portal in San Francisco, Palo Alto, and Beverly Hills are preserved in amber by NIMBY homeowners.

Real estate investors from across the globe are buying up these newly attractive urban neighborhoods while they’re cheap, evicting low-income families and building high-end new developments without any affordable units to reap massive profits as the neighborhood gentrifies and land values double and triple. Whenever government sends a signal to the market that a certain historically low-income area will be “revitalized” through re-zoning, incentives, or other policy changes, it sets off fierce competition among investors for that patch of land, with prices spiraling upward precisely because the market expects them to. SB 827 would have contributed to this speculative bidding war, increasing the expected future property values in gentrifying low-income neighborhoods across the state by sending a clear signal that these were the prime zones of new development in California.

Outside of San Francisco, the bill would not have dramatically impacted many of the wealthiest low-density enclaves in Silicon Valley and West LA that were often used by the bill’s proponents as examples of the NIMBY problem that needed to be solved. Many of these communities have fought for generations to keep out mass transit just as they’ve fought to keep out affordable housing, and so a bill increasing housing density near public transit would have resulted in relatively little change there.

In many cases, the bill may have worsened many of the problems it aimed to solve. What happens when a neighborhood like South LA, with many low-income families who commute to work daily by public bus out of financial necessity, are replaced by transit riders of choice who see having an apartment near a light rail stop as a desirable amenity, but when it’s hot out, or they’re running late, or just feeling lazy, can afford to hop in an Uber instead? Many cities making historic investments in transit infrastructure and transit-oriented development are actually seeing transit ridership decline, likely due to gentrification displacing low-wage workers to distant car-oriented communities with more affordable housing. Wealthier people also consume more housing per capita. When a neighborhood gentrifies, often the existing housing stock is used less efficiently, as an immigrant family of six living in an apartment is evicted to make room for a childless couple of young professionals who can afford higher rent. In fact, gentrification actually decreases both urban population density and transit ridership by pushing families out into exurbs or even out of state altogether, making poorly-designed transit-oriented development plans counterproductive.

Development Effects: Regional vs. Localized Impacts

New development in urban gentrifying neighborhoods might help increase the overall regional housing supply to accommodate the influx of young professionals to the regional job markets of the Bay Area or Southern California. However, the actual communities slated for development can certainly expect their neighborhood rents to increase, not decrease, as mid-century low-rises built decades ago for factory workers and their families are bulldozed or renovated into luxury housing marketed to millennial tech employees along with the high-end amenities that follow them. While new housing in edge neighborhoods in Oakland might make a dent in the regional jobs-housing imbalance of the broader Bay Area, at the neighborhood level, these new developments often tend to increase the land values around them by signaling that this is an “up and coming” neighborhood. The strategy at the heart of SB 827 essentially would have sacrificed the urban neighborhoods of working-class people of color — by making housing there less affordable — for the cause of increasing regional housing supply. It is hardly a surprise that the residents of those communities weren’t thrilled to learn about the proposal.

When proponents of SB 827 were confronted by communities of color concerned that the legislation would further drive the gentrification of their neighborhoods, they were too often met with tone-deaf dismissive arrogance, such as during a rally in San Francisco where black and immigrant tenant activists were shouted down with chants of “read the bill.” Community organizations did read the bill, and they did not like what they saw. It is often implied that the criticisms of working-class and people of color tenants are the result of simple ignorance of the housing market economics. In reality, longstanding communities of color often have much deeper understandings of urban housing dynamics based on lived experience, particularly their speculative and unequal nature, after watching their whole neighborhoods be displaced by private market redevelopment or “urban renewal” schemes. Over decades, these communities have been become distrustful of proposals that purport to help them while in fact providing very few benefits.

Rebuilding that sense of trust is essential to making sure these communities and housing advocates can work together to come up with solutions that protect vulnerable tenants, preserve affordable housing, create employment opportunities through quality jobs, and produce more housing especially in exclusionary communities. Housing supply advocates seeking the support of the most impacted communities should stand in solidarity with these communities’ struggles for protections like legal aid for tenants facing displacement, stopping landlord discrimination in housing applications, and setting clear limits on the rising tide of rent increases and evictions. These policies are necessary to provide immediate relief to the people in the most urgent need, to preserve the existing supply of affordable housing and neighborhoods, and to curb the out-of-control spiral of land speculation in gentrifying neighborhoods. Setting basic job quality and community benefits standards for development may be another small hurdle for developers, but it ensures that local working-class families actually benefit from the jobs associated with construction in their cities.

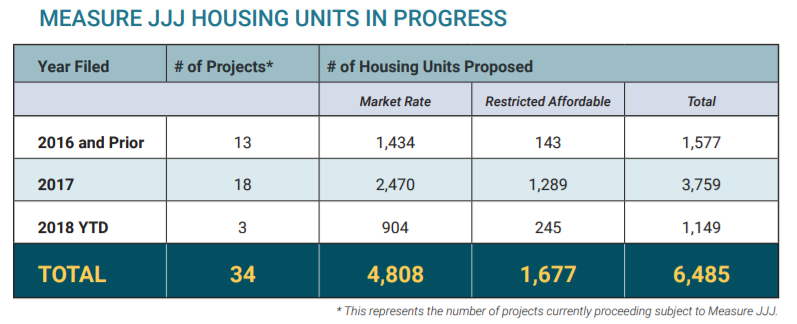

Working-class communities of color have in fact led the way to better models of building housing near transit through Measure JJJ, overwhelmingly approved by Los Angeles voters in 2016, and the city’s Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) Affordable Housing Incentive Program, which is increasing housing density near transit investments while guaranteeing affordable units and job quality standards. This approach allows communities of color to exercise the power and agency that decades of exclusion and disinvestment robbed them of. These policies encourage increased density, new affordable housing construction and good local construction jobs, and since fall of 2017 have led to 146 distinct proposed development projects totaling 12,056 total housing units — including 2,822 units of subsidized affordable housing.

Moving Forward: An Equitable Policy Agenda

To be able to enact transformative housing policy this time around, proponents of SB 827 must be serious about engaging with, listening to, and following the leadership of low-income communities of color fighting to remain in their neighborhoods. That means doing three things: developing policies with the communities most impacted by California’s housing crisis at the table and in leadership, prioritizing historically exclusionary communities for new development rather than communities at risk of displacement, and thinking beyond market solutions by advancing policies to curb speculation and create large-scale permanently affordable housing.

First, good policy starts with good process. While policymakers often struggle to effectively engage with marginalized communities, luckily California has a rich ecosystem of grassroots community organizations with deep relationships and membership bases among the working-class people of color on the front lines of the housing crisis. Statewide networks like PICO, ACCE, Tenants Together, California Calls, the Partnership for Working Families, and more, represent the voices of millions of Californians most impacted by gentrification and displacement. The assumption from some SB 827 proponents has been that our communities have not offered serious solutions to the housing crisis or that we are allied with rich homeowners to block development. We have offered equitable, expansive solutions to the housing crisis, often against the interests and the votes of California’s landed gentry. The reality is that our solutions and ideas haven’t been implemented because our communities are systematically disempowered and marginalized from the legislative and development process. And many of our most basic policy proposals, like the right to not be arbitrarily evicted without a just cause, are still unable to succeed in Sacramento because of the crushing power of landlord lobbyists.

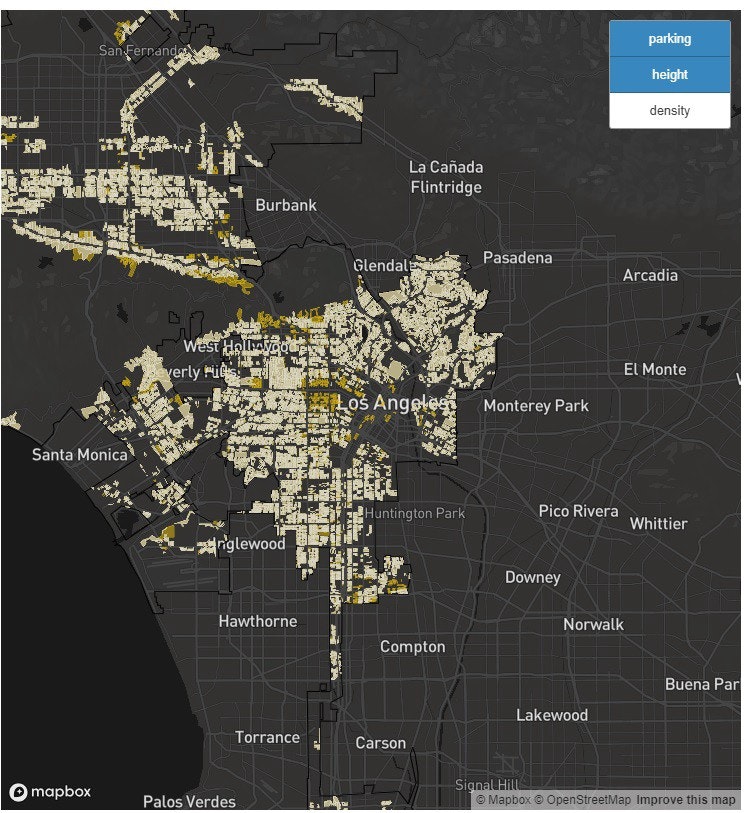

Second, while solving California’s housing crisis certainly involves building more housing, the critical questions are where and how. Sacrificing California’s communities of color through displacement from our neighborhoods to make room for new development is both morally wrong and counterproductive. This removes our cities’ greatest pools of naturally occurring affordable housing and replaces working-class communities of color with residents who consume more and pricier housing and rely on transit much less. We should look to build in communities with high-income job growth, lower population densities, large jobs-housing imbalances, and histories of falling far short of their Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) goals. The communities that should be required by the state to upzone and build affordable housing are places like Palo Alto and Santa Monica that are booming with high-tech jobs but refusing to build the housing necessary to accommodate their workers, and places like East Oakland and South LA, the last refuges of affordability for our cities’ low-wage workers, should have the resources to plan for growth on their own terms. A statewide geographic scoring mechanism taking into account several measures of housing exclusion could determine where to focus increased density, relaxed parking requirements, and other incentives for new development and which communities should be prioritized for additional protections against displacement, preservation of existing naturally affordable housing, and resources to plan for additional housing.

Third, we believe that private market-based solutions are not sufficient to reach the scale needed to solve our housing crisis. This is as true today as it has been throughout our country’s history. In the postwar era, as millions of white Americans fled the urban core to start families in the suburbs during a new age of economic prosperity, massive federal, state, and local government spending was devoted to creating whole new communities and subsidizing homes there, giving birth to the American suburbs. Even though they included explicitly racist components, legislation like the G.I. Bill and the Housing Act of 1949 invested billions of dollars in middle and working-class housing. If a post-industrial knowledge economy requires a return of millions of high-income professionals away from suburban sprawl and back to the city centers, the private market alone is unlikely to build this housing without mass displacement of working-class people of color. Addressing the housing crisis of our time in an equitable way will require another historic investment of public resources to advance the public good by creating a broad range of housing that is affordable and accessible to people of all income levels. We will need creative ways to finance this housing, like regional commercial linkage fees, head taxes, land value taxation, and large-scale bonds to build mixed-income social housing. These solutions address not only the historic disinvestment from public, social, and workforce housing but also move us toward making housing a human right instead of a speculative investment.

Working Together: Both/And Approach

We know that proponents of SB 827 intend to try again to pass bold and disruptive housing legislation in 2019. To create a more successful and more equitable breakthrough for California’s housing crisis, they’ll need to build authentic relationships with the organized leadership of the state’s communities of color, be brave enough to challenge the real hotbeds of exclusion, and rethink the dogma of market-driven housing economics being put forth by the wealthy and powerful real estate industry. Truly tackling the housing crisis will require joining together to take on far more powerful enemies: entrenched NIMBY homeowners, the California Apartment Association, and unscrupulous low-road developers. But only with the support of a far more inclusive coalition of allies will it be possible to overcome generations-long legacies of injustice and make sure that we can both protect the most vulnerable among us and continue to welcome all who want to live here. Together, we can build a California for all of us.

TL, DR

- YIMBYs and Working Class Communities of Color should work together to take on NIMBYs.

- Equitable growth policy must have affordability, labor standards, and geographic balance at the center.

- We have to push for models and policies that protect current renters, welcomes new people of all incomes, and unlocks exclusionary communities through renter protections, social housing models and incentive-based market housing.