Last month our affiliate, Warehouse Worker Resource Center (WWRC), supported people working at Amazon’s KSBD air hub in San Bernardino as they walked off the job to demand better pay, safe working conditions, and an end to retaliation. The workers organizing at KSBD are known as Inland Empire Amazon Workers United (IEAWU). This month Vincent Acuña (Campaign Coordinator for Worker Power and Corporate Accountability) talked with Sheheryar Kaoosji (executive director of WWRC) and two members of IEAWU, Sara Fee and Ricardo Perez, about organizing warehouse workers and communities in the Inland Empire.

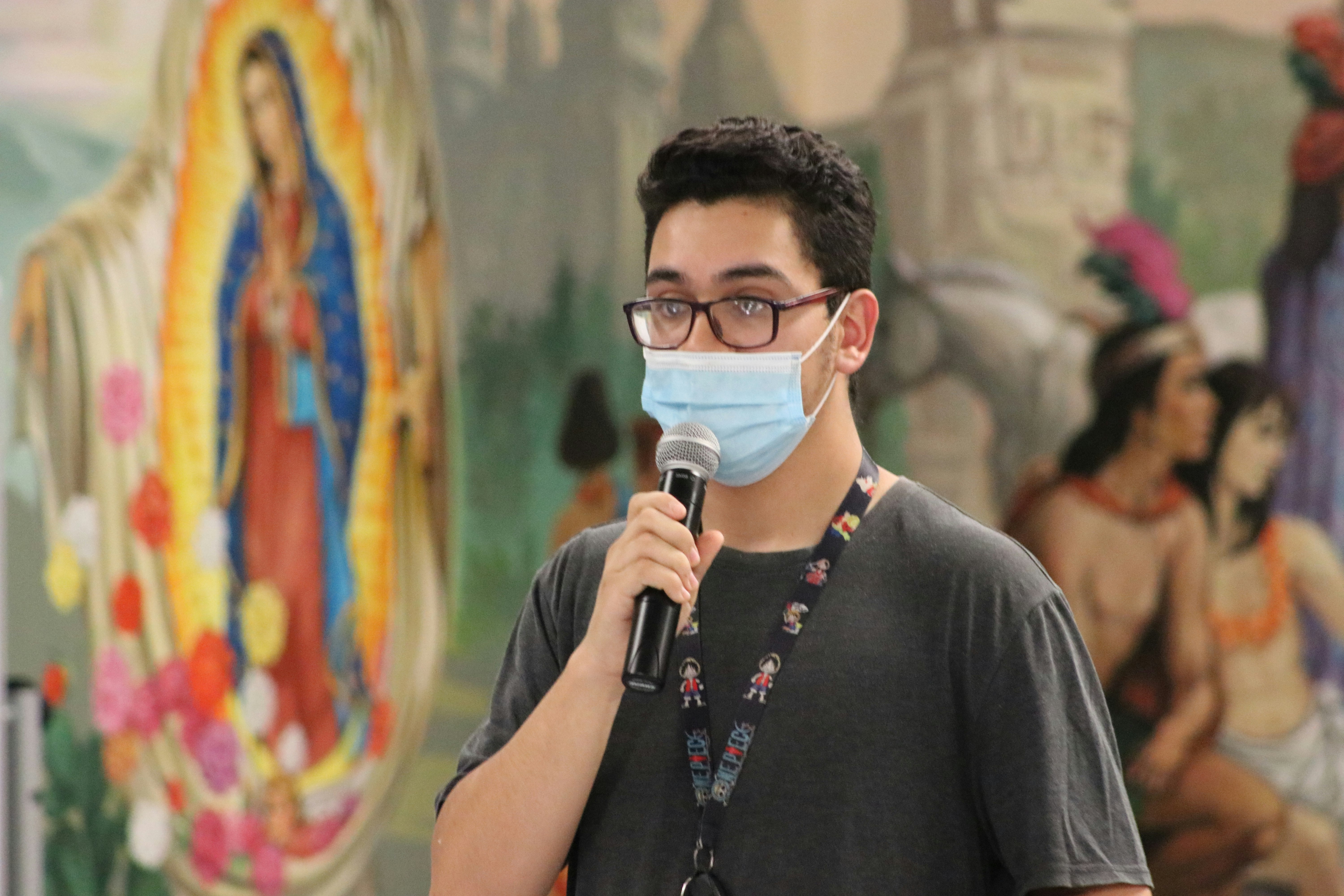

Vincent: Thank you all for making the time to talk about the worker and community organizing efforts in the Inland Empire and beyond. Sara and Ricardo, can you share what brought you to Amazon and what your experience at KSBD has been like?

Ricardo: I've lived here in San Bernardino, in Highland, pretty much my entire life. I started working at a different Amazon facility, ONT5, which is down the street from our current building. I worked really hard there. I would hurt myself and try to shrug it off or walk it off. I came to KSBD with a different mentality, but I’ve lost faith in the Amazon system. I need to work all these hours just to afford my bills, to pay my rent, to eat my food. We work for the biggest company in the world and we're struggling to pay for our basic necessities.

Sara: I moved to San Bernardino about a year and a half ago. Amazon was hiring in mass and I literally had a job there within two weeks. We were taught to move fast: “The pressure's on. Go faster. Let's change the process. Let's make it faster.” For the longest time my department had the best numbers. That was the culture in my department and in the rest of the building. There were a lot of people getting hurt. Now as I’m involved in organizing, I feel retaliated against every day. I'm treated differently than I was before, and that affects my mental health.

Vincent: Sheheryar, can you share some of the history of the region and Amazon's efforts to expand their presence there?

Sheheryar: The first Amazon warehouses in California were built in 2011 in San Bernardino, which is the poorest city in the state and one of the poorest cities in the country. It has been economically ravaged by a lot of different forces and, not coincidentally, it is one of the cities with the highest populations of communities of color in the region and the state. When Amazon opened its first warehouse in the area, San Bernardino was just going into bankruptcy. The corporation was seen as a savior in terms of bringing jobs to the region during a really rough time for the economy. Amazon was a big name that promised good jobs, when in fact they turned out to be low quality, high turnover jobs with high injury rates. Since then, Amazon has expanded to where it is now the biggest private employer in our region. It's actually the biggest private employer in the state of California.

Vincent: Thanks for that context! How is Amazon impacting not only workers, but the communities that they’re in?

Sara: There's Amazon trucks everywhere, all over the IE. You see delivery vans, big rigs, you see it all every day. The streets are beat up in San Bernardino, there are potholes everywhere. And our air quality is terrible, freaking terrible. There's soot on the sides of our buildings. We're breathing that stuff in and it's not just on the outside, it's on the inside, too. I feel like there's a layer of dust on everything. That has an impact on our health even when we're outside of the building. Before I got involved in organizing, I had Amazon Prime, Amazon Music, I was ordering stuff. Now I can't do it. It feels wrong. I can't give Amazon any more.

Sheheryar: Warehousing in general has manifested itself as an economic opportunity for communities, especially communities that are historically disadvantaged or poorer, which tend to be the places where there's more industrial land. The IE is a typical example of an area outside of the urban core, where there's a lot of working class people and people of color who are hoping for opportunities. Even if you don't work in the sector, you are impacted. Either someone in your family works there or you work there at some point. Like Sara mentioned, the San Bernardino area also has some of the worst air quality in the world, especially the areas that are really close to rail yards and warehousing, which are low-income BIPOC communities.

Vincent: How has WWRC been bringing workers and community members together to challenge Amazon’s impacts and make things better for everyone in the Inland Empire?

Sheheryar: The term “warehouse worker” is a little fuzzy because the industry burns through people so quickly. You're a warehouse worker one day and then you're not. You're a warehouse worker for a few months, then you're in construction, then home care, then a restaurant, and then you're back in the warehouses. That's the life of a working person in the Inland Empire. The “warehouse worker” identity is both broad and also kind of thin. That's something that WWRC has really leaned into and acknowledged. Whether you’re working in a warehouse or not, you and your family are affected either way because warehousing is the dominant employer in our region.

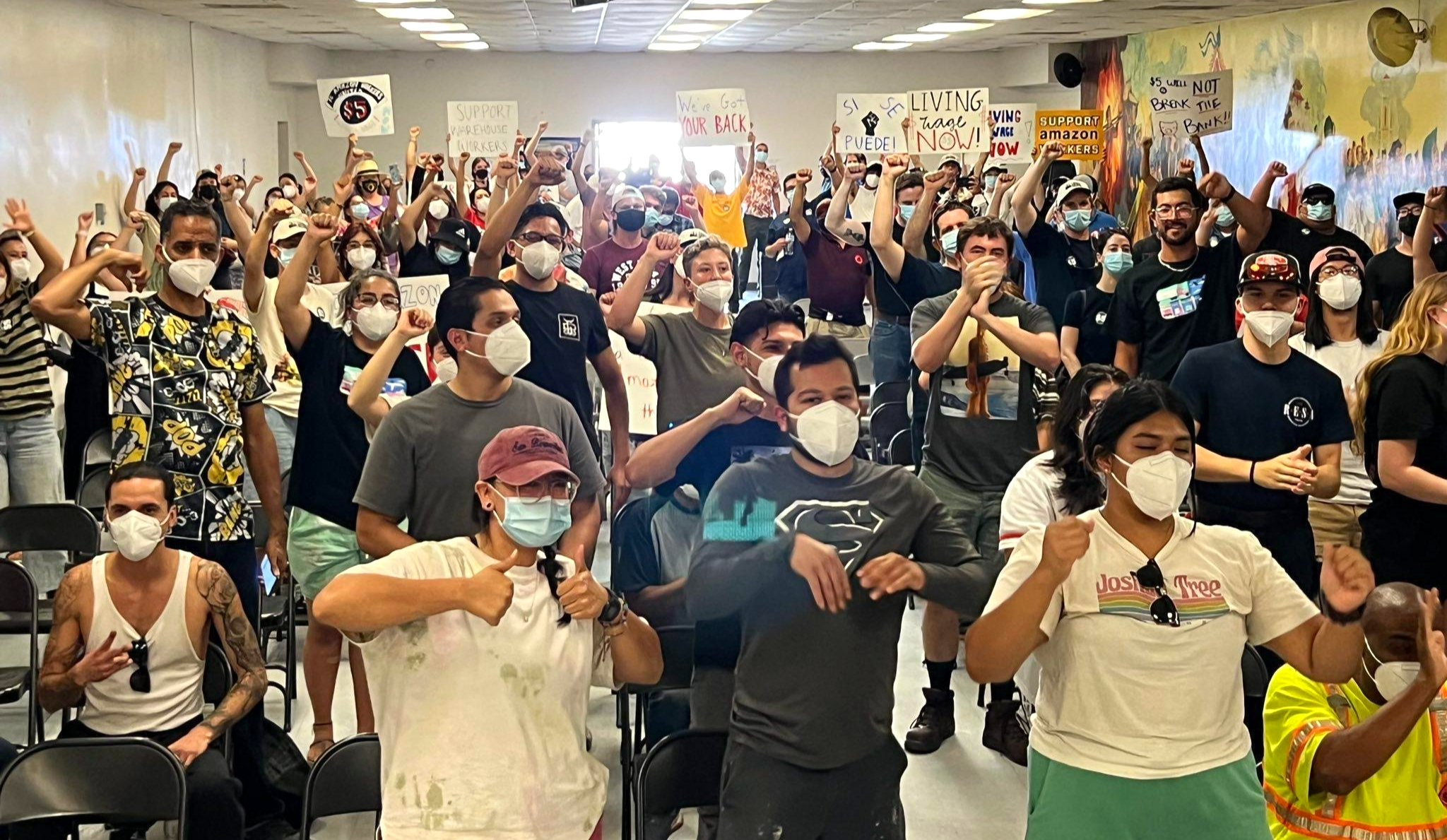

So, we organize around the whole person and their family. We acknowledge that building community in this region is a revolutionary act. Our region was designed with very little public space, with few opportunities for people to connect with each other. It makes civil society difficult. What we're trying to do is, first and foremost, rebuild spaces for civil society where people can get together. So when we have a picket line or a rally, people come out because they see the warehousing industry as something that dominates their community, even if they don't necessarily work in a warehouse.

Ricardo: After the KSBD walkout, we saw the amazing support, not just from WWRC, but from at least 10 different groups there supporting us. It was really incredible.

Sara: Regular community members just want to be involved in making their community better. They're taking time out of their life, out of their family's life, and they're showing support for what we're doing and we're super thankful for that.

We're all facing something at work. Everybody has some kind of issue they're going through. What brings us together is that common ground, so don't be afraid to talk to the people that you work with because you're going to have common issues. There are going to be things that you can identify with. Those are the conversations that make us stronger.

Sheheryar: The industry has really run rampant, but in the last 10 years workers and the community have started to ask for more. The environmental justice movement has also focused on the sector to say that conditions here are not an accident. This is a very intentional system that's been developed here and we can and should get a better deal. That's been the narrative over the last few years. Then the pandemic essentially put a big underline under it all. It became really clear to everybody what side of the line they're on: who is making money and who is not.

Vincent: Why is the Inland Empire such a strategic place to have this fight against Amazon’s abusive practices?

Sara: We make those packages move. Without us, they don't go anywhere. I think we should be given a certain level of respect. I would like to see that culture in Amazon change. If you're just a regular associate, you should be treated like you matter.

Sheheryar: Without the Inland Empire, people don't get their products. Without the people who work here, people don't get the stuff that they use to survive. At the same time, people in the region haven't gotten their fair share. Workers are not properly supported for all the literal labor they do, but they’re also facing health and safety impacts from being in an area that is polluted mostly because of the goods movement sector. So we see it as a racial justice fight and we see it as an environmental justice fight inherent to the region. We see the goods movement sector as fundamentally a colonial power extracting labor and resources, and literally extracting people's health. We also see that there's a different path. It could go a different way.

Vincent: How is IEAWU connected to nationwide fights for better working conditions, and how is WWRC supporting that effort?

Sheheryar: We knew that San Bernardino is a site of a lot of conflict around goods, movement, and warehousing. Once we heard from the workers at KSBD, we started supporting them, helping them access organizing resources and tools, but also understanding the context of what's going on at Amazon. They know that they can't do it alone, but also that they're not alone. They have a really smart and robust organizing plan inside. WWRC’s role is to make sure that they’re connected to what's going on across the rest of the country.

Sara: There is this whole labor movement sweeping the entire country right now. There is a lot of support and the more we connect with other groups trying to improve their workplaces, the stronger we all are together. The more of us who are willing to say, "We're not going to be treated like this anymore," the stronger we are. We're building that strength inside the building in spite of Amazon's efforts, and we're building that strength outside the building.